- Home

- Onuzo, Chibundu

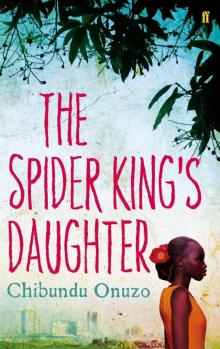

The Spider King's Daughter

The Spider King's Daughter Read online

The Spider King’s Daughter

Chibundu Onuzo

This first fruit I dedicate to my Father in heaven

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

Chapter 1

Let me tell you a story about a game called Frustration. A dog used to follow me around when I was ten. One day, my father had his driver run this dog over in plain view of the house. I watched from my window. The black car purring on the grit, the driver’s hands shaking as he prepared himself for a second hit and my father, sitting in the back seat, watching.

The car reversed. Again his tyres rolled over my dog and then he sent for me.

I was calm until I reached him, his head bowed in the black funeral suit that he wore throughout my childhood, his arms folded.

‘I’m so sorry. I know how much that dog meant to you. I don’t know how this idiot didn’t see it.’

I knew he was lying. He knew I knew and in that moment, I felt an anger fill me, so strong it would surely have killed one of us if I let it loose. Somehow, it was clear to me that this would be the wrong thing to do. I strolled over to the dog and prodded it with my foot. Blood had streaked its fur and it was whining in pain. My father studied my face, searching for the smallest hairline of a crack. I just stood there, looking at the animal.

Finally I said, ‘Daddy, please can we run over my dog again?’

Both he and the driver were visibly shocked. My father nodded. The driver shook his head, his knuckle bones popping out of his dark skin.

‘Do as she says.’

‘Aim for the head,’ I said, leaning against the car and taking a perverse pleasure in the driver’s shrinking away. I turned and walked towards the house in that stroll that children have on the first day of their summer holidays. I called over my shoulder almost as an afterthought, ‘Daddy, please make sure he hits the head this time.’

Abikẹ: 1

Mr Johnson: 0

Every morning I wake up and know exactly what I have to do.

1 Bathe.

2 Make sure Jọkẹ does the same.

3 Eat breakfast.

4 Make sure Jọkẹ does the same.

5 Ditto my mother.

6 Take Jọkẹ to school.

7 Leave school for work.

8 Make sure Jọkẹ never does the same.

It has been my morning routine for about two years. Lately, it has become more difficult to make number 5 happen. She cries when I ask her to eat. I have his voice, Jọkẹ tells me, so my mother’s salty tears drip on to the slice of bread meant for breakfast. This morning when we left, she was still in her nightie with her hair scattered from sleep. There was a time she would have hated anyone to see her looking like this. Now she is like a tree in the dry season. Every day a piece of her old self falls off.

‘Bye, Mummy.’

‘Have a good day at school, both of you.’

I have told her that I don’t go any more but sometimes she forgets. Once I shut the door, Jọkẹ came to life.

‘Did you know Mrs Alabi had a baby? The one that lives there,’ she said, pointing at a peeling door. ‘It was a boy and she is very happy because finally her in-laws will leave her alone.’

‘Jọkẹ, I’ve told you to stop listening to gossip.’

‘It’s not gossip if Funmi told me.’

‘Who is Funmi?’

‘Don’t you remember Mr Alabi’s daughters, Funmi, Fẹmi and Funkẹ? They came to the house when we moved. You didn’t like them. You said they wore too much make-up. It’s only Fẹmi that wears too much. The others are OK.’

We were by the main road preparing to cross. A few feet away, there was a footbridge. We had not taken it since the first day I walked Jọkẹ to school and found my pocket empty on the other side. A red Toyota passed, then a Benz, then a small break. I gripped Jọkẹ’s hand as we dashed across.

‘Don’t talk to those girls,’ I said once our feet touched the pavement.

‘Why not?’

‘Because I said so and I’ve seen one of them smoking.’

‘Which one?’

‘Her name started with F.’

‘All their names start with F.’

‘I know.’

‘Why won’t you tell me? I won’t tell because last time you told me something and told me not to tell—’

As she talked, I watched Wednesday, a regular hawker on this route, chase after a black jeep with his sales rack clutched to his chest, his muscular legs pounding down the road. The driver was teasing him. Slowing down and then speeding up, moving towards the highway with Wednesday’s money. For a moment, it seemed like Wednesday would make it. The moment passed. Slowing down into a jog and then an amble, he continued walking in the direction of the vehicle, unwilling to believe that the owner of such a fancy car would steal. As the jeep sped on to the highway, naira notes, like crisp manna, floated to the ground.

Bastard.

‘Are you listening to me?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then what’s your answer?’

‘To what?’

* * *

A man in a yellowing starched shirt shoved past, nearly pushing us into the road.

‘Look, Jọkẹ, I have to watch the pavement. This place can be dangerous.’

‘Fine! Don’t listen to me. I’m going to Obinna’s party.’

‘Who is Obinna?’

‘I just told you!’

‘Well, whoever Obinna is, you’re not going to his party.’

When had she become old enough for parties? I had taken her to the market to buy her first bra and sometimes I woke to find red spots on her side of the bed. Still she was only fourteen, barely a teenager.

‘Whatever. I don’t like Obinna anyway. He has too many pimples.’

I took her hand again and was grateful when she did not pull away. Too soon we were at the gates of her school. She drifted forward, looking for her friends.

‘Have fun at work.’

She said this every day though I had never explained to her what I did. Trader was the vague description I had given to my job and she had never probed.

‘Have a good day at school. Make sure you wait for Miss Obong.’ I had arranged for Jọkẹ to walk home with her English teacher who lived near our block.

‘Do I have to? Everyone goes home by themselves. I look like a baby.’

‘You have to.’

‘I’m stopping

once I turn fifteen. Deọla!’

She shouted and was gone, running through the gates.

Chapter 2

I don’t usually buy things sold on the road. A hawker I met today made me break my rule. Our eyes caught in traffic and that was all it took for this boy selling cheap ice cream to start approaching my car. I turned my head but he continued to advance. A gap opened in traffic. My driver crawled across the space.

‘Drive on.’

‘Don’t you wan buy something?’

‘Drive on.’

My driver sped up. The hawker gave chase. Traffic eased up and we found ourselves skimming along the road. In the side mirror, I could see a figure running after us. Another fifty metres and the figure was still there, although smaller.

‘Slow down.’

‘Eh.’

‘I said slow down.’

This hawker was a fast runner. There were only ten metres between us.

‘Speed up.’

‘Eh.’

‘Speed up!’

The car jerked ahead. Now the idiot was going too fast. I could see the hawker disappearing behind us.

‘Slow down! Slow down!’

My driver pressed his foot on the brake bringing the car to a sharp standstill. I grabbed the armrest but the momentum pitched me to my knees.

‘Aunty, sorry o.’

‘Can’t you follow the simplest instructions?’

As I struggled back into my seat, my elbow pressed a button and the window slid down.

‘But—’

‘But what? Don’t you listen? I didn’t tell you to stop.’

‘I no understand.’

‘Idiot! I said slow down.’

I turned to find the hawker beside my car. He was very good-looking. Dark and chiselled like something out of a magazine. I glanced at what he was selling. Sugary milk, frozen and wrapped in plastic for distribution to the masses.

‘May I have one, please?’

‘What flavour?’

‘Vanilla.’

‘One hundred naira.’

I stuck a two-hundred-naira note out of the window and waited. You never pay a hawker until you have what you’re buying firmly in your hand. I was given my change first, then my ice cream.

‘Thank you.’

When he left, traffic had descended again, leaving every vehicle pressed against another. Once I was certain he was gone, I flung the plastic thing out of the window.

‘Tomorrow, take this way home.’

There was a time I wanted to be a lawyer, though of a different kind to my father. He was a bad speaker, rarely went to court and had a squint from reading the small print of contracts. It was his colleagues who inspired. Sometimes they visited our house still in their black gowns, coming straight from a case I had read about in that morning’s newspaper.

Law was not to be. Instead, I am a hawker now, a mobile shop, an auto convenience store. I have grown used to the work. There are days when the rain is so heavy that the water rises to my knees. Other times, peoples’ tyres squash my toes and often people call me and then refuse to buy. I have learnt to appreciate the few customers who treat me like a human being.

There was a girl I sold ice cream to today. She was sitting in the owner’s corner of a jeep although she was too young to have bought the car. Her small body leant against the door leaving most of the back seat empty. While I was observing her, she looked up. Briefly our gazes held and before she could look down and dismiss me, I strode towards her with my sack of ice cream. When I was a few feet away, traffic mysteriously disappeared. The jeep zoomed ahead.

I gave chase. Half-heartedly at first but when I saw the car slow down, I picked up speed. Ten metres from the jeep, it sped up again. I kept running. The car was beginning to diminish and so was my anger. Then the car slowed down. Something cracked inside me and all I wanted was to spit in the face of the girl in that back seat. Stringy, phlegmy, spit that would run down her shocked face. Once I was a few feet away, I knew saliva would be the last thing coming out of my mouth.

I heard shouting. It was coming from the jeep. I moved closer. From the back seat, the girl clearly said, ‘I told you to slow down!’ Suddenly everything was all right.

‘May I have one, please?’

‘What flavour?’

‘Vanilla.’

‘One hundred naira.’

I looked at her face while she was bringing out her wallet. Her skin was so smooth I wanted to slide my finger along it. She passed me a two-hundred-naira note with a smile that showed her perfect, white teeth. It would have been so easy to sprint off with her money. I gave her the change before placing the ice cream in her palm. Someone else would have to show her that the world was not filled with honest hawkers and unicorns.

‘Thank you,’ she said. Words I don’t hear often. I nodded and walked back to the side of the road.

Chapter 3

‘Funkẹ, which university are you going to?’

‘My mum thinks I should choose Brown but I think it’s too expensive. The tuition fees alone are forty thousand dollars. What about you, Chisom?’

‘I think Duke. Their fees are even higher.’ The whole class could hear the triumph in her voice.

‘So, Abikẹ,’ Funkẹ said, turning to me, ‘have you decided where you’re going?’

‘Yale.’

The good thing about applying from Nigeria was that most of the process could be done by someone else. My father had paid a PhD holder to fill out my forms and sit the SATs for me. I had taken the exams under a different name and been pleased to see that my score would have been adequate.

‘Wow. So, Abikẹ, how much are Yale’s fees?’

‘It doesn’t matter, Chisom. The cost makes no difference to my dad.’

Forest House was filled with people like these girls: a little money, a lot of noise.

* * *

‘Settle down, class, settle down.’ Mr Akingbọla bustled in, his trousers gripping his buttocks. ‘I said, settle down.’

Someone at the back shouted, ‘Bum-master in the building.’

‘Who was that?’

He turned to face us with his large nostrils flaring. ‘I said, who was that?’ He slapped the teacher’s desk. ‘Don’t let meh hask hagain.’

When Mr Akingbọla was agitated, he spread his aitches freely. This always made the girls titter and the boys copy their fathers’ deep laughs.

‘Hexcuse meh, sir, have you travelled before?’

‘How can he? He’s too endowed for the plane seat.’

Again another wave of laughter swept through the room.

‘Silence. Can you talk to your fathers like that?’ He was fast descending into his trademark rant. We were spoilt, we were useless, we would never amount to much.

‘Even if your parents are successful, you—’

Already, half the lesson was gone. A paper plane flew through the air and landed on his desk. This was getting ridiculous.

‘Listen to Mr Akingbọla.’

I needed only one person to hear me.

‘Listen to Abikẹ.’

‘It’s true.’

‘Some respect, please.’

‘Yeah.’

The class fell quiet.

‘You will not succeed.’ Mr Akingbọla’s voice rang out, our sudden silence reproaching him. He shuffled his papers, arranging and re-arranging until he was calm.

‘Today, we are going to continue our lesson on titration. When we want to find out the acid concentration of a substance this process can be used. What other processes can it be used for? Chike.’

Chike answered and Mr Akingbọla droned on, the questions that followed every statement always managing to miss me. I felt no need to display my knowledge. On previous occasions, when he had put me on the spot, the class was allowed to become uncontrollable. He learnt fast.

‘Next week,’ he said in closing, ‘we are going to conduct a practical experiment on acid-base titration. Make sure you .

. .’

I wonder if the hawker will be on the road today.

The Datsun stopped abruptly, narrowly missing my legs.

‘Clear from there,’ the driver said, banging on his horn.

‘Are you mad? You no dey see road?’

‘My friend, comot or I go jam you.’

‘You dey craze? Oya jam me.’

‘Comot.’

‘I said jam me today.’

The man swerved into the next lane.

‘Idiot.’

‘Your mama,’ I spread the five fingers of my right hand and spat.

Fire for fire: that is the only way to survive on the road. When I first started I used to mind my manners. Yes please, no thank you, like my mother taught me, but those manners were for a boy who was meant to go to university and work in a law firm. She never told me what to do if a customer sprinted away with my money. She never gave me advice on how to handle the touts that came here sometimes asking for ‘tax’. I had dealt with one that morning, a slim, feral-looking man.

‘Trading levy,’ he had said.

‘I don pay your people already.’

‘Nah lie.’

‘I tell you I don pay. No harass me. They know me in this area.’

‘Who are you?’

‘You don’t know me?’

He was clearly a newcomer unattached to the main body of touts or he would have called my bluff. Instead he spat and moved on to the next hawker.

‘Trading levy.’

I looked round and saw that there were only a few of us left on the road. Traffic had eased which meant that it was time for our break. To save money, I rarely bought lunch outside but I liked to sit with the boys while they ate.

‘Runner G,’ someone said, announcing my presence to the group. They raised their heads from plates piled with rice and red stew, the cubes of meat almost invisible in the mounds. I slapped some palms and rubbed a few backs before joining the circle of hawkers.

The Spider King's Daughter

The Spider King's Daughter